Confessions of a Chronic Rewatcher

A Date With George Saunders, Dante, And Why I Keep Going Back to the Same Films

In A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, George Saunders doesn’t just dissect Russian short stories—he shows us how to read them attentively. The point isn’t academic; it’s practical. If you read slowly, pausing to ask what’s happening, what’s working, and what’s being hidden—you not only understand the story better, you understand how stories work.

That’s how I’ve come to think about watching and rewatching movies. Not as indulgence, but as practice. Each rewatch lets me slip into a different layer of the film, peeling it back the way Saunders peels back a page of Chekhov or Tolstoy.

The first time through, I let myself be pulled along and fully immerse in story. Take the ride, as they say. The second time, I look for what I missed. By the third or fourth, I’m paying attention to craft and performance, the small, human details that might have slipped past me before. If I’m rewatching more, it’s because I love the film, have become obsessed with it, and start finding things that I even find unintentionally funny or just so moving that I need it again.

I take a similar approach when reading scripts. I try to separate the actor/writer from reading the first pass. I simply read the story. But when it’s time for script analysis, I’m paying more attention to the fine details of environment, character, and language. I’m also actively considering Dante’s 4 Levels of Literary Interpretation:

Literal

The story as it is told, with its characters, events, and settings.

Allegorical

Any symbolic meaning, often tied to moral or theological truths.

Tropological

Moral or ethical lessons or guidance for how the reader should live.

Anagogical

The highest level, pointing toward ultimate spiritual realities: salvation, eternity, the soul’s union with the divine.

By allowing myself to read a text considering these four interpretations, I give myself as many tools and “in’s” to the story to make it real to me when I get on my feet and start rehearsing.

Dante and Saunders remind us that reading with attention transforms us—not just as writers or artists, but as people learning how to pay attention at all. Watching film can work the same way. You don’t have to rewatch obsessively, but if you watch with intention—even just once—you start to see the world of the film, and maybe your own, with new eyes.

In a day and age where attention spans have dwindled, our Micro vs. Macro attention has been commodified by fast food entertainment, Tik-Tok, and Instagram videos. Recently these social media platforms have even added a feature where we can watch in double time—because a one-minute video is still too long for us to stay focused. And the point of that is not because we want the video to get to the point; it’s because we want to get to the next video and the next.

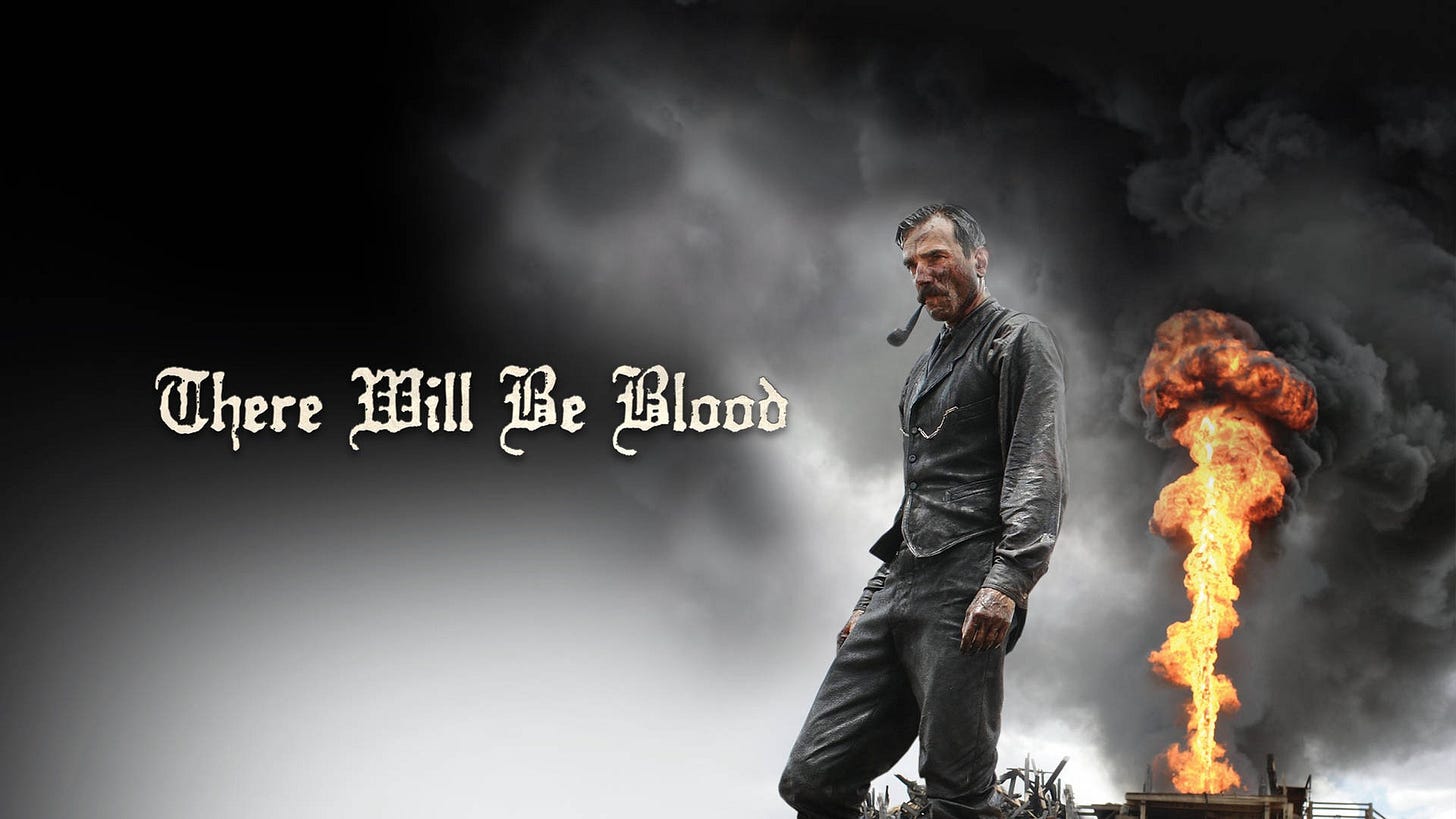

Here's an example of my watching and rewatching process, using one of my favorite films:

First Watch: Immersion

On my first viewing, I was consumed by the story—Daniel Plainview clawing his way to power, the tension with Eli Sunday, the brutality that builds like oil under the ground. It was visceral. I wasn’t thinking about camera angles or motifs. I was just swept up in the hunger and rage. It’s also hard to keep your eyes off DDL in anything he does, so it makes sense if you are completely swept away watching him.

Second Watch: What I Missed

I notice how many little signals I’d skipped. The wordless opening, where the story tells you everything about Plainview’s ambition before he ever speaks. The quiet moments with H.W., how even then, the shadow of business creeps in. It wasn’t just a story about oil—it was already a story about isolation.

Third Watch: Craft

I’m watching the craft. Robert Elswit’s cinematography—the frames that stretch out like paintings. The way Jonny Greenwood’s score sounds less like music and more like a nerve humming. The cuts that land like blows. The film became less a narrative and more an orchestration of sound and image.

Fourth Watch: Performance

I’m deep diving actors/characters. Daniel Day-Lewis. The way he modulates his voice from silence to thunder. How his posture changes when he’s performing for a crowd versus when he’s alone. Even the tiniest gestures—his glances, his silences—start to tell their own story. There are the obvious scenes (I drink your milkshake! and I’ve abandoned my Child!) but there is another scene I obsess over.

Fifth Watch and Beyond: Play

I’m no longer just watching the film—I’m living inside it. I’m the person mouthing lines before they’re spoken (I promise I do not do this if I’m watching with someone else), pausing and rewinding to savor a moment, or finding humor in places no one else would think to laugh. The characters’ emotions—joy, fear, despair, longing—are ones I’ve felt myself, and there’s a strange comfort in meeting them again on screen. Rewatching, at times, can feel like a kind of coping, even a trauma response. But more often, it’s a form of solace. It’s the same reason we put on familiar sitcoms in the background: they become a kind of home we can return to, a place where repetition feels safe.

Using this process, here’s a breakdown of one of my favorite scenes:

A campfire scene between Daniel Plainview and his supposed half-brother. It’s quiet, almost tender on the surface, but underneath it’s about Daniel exposing his inner void.

He sits across the fire from Henry and begins to speak—almost unprompted—about who he really is. For a man who spends most of the film manipulating, performing, or raging, this is the closest he comes to confession.

He says, essentially: I hate most people. He admits he doesn’t see much in others worth liking, that he wants to succeed so badly he doesn’t want anyone else to succeed. He even admits to struggling with “these people”—his investors, neighbors, competitors—because all he can see in them is weakness or threat.

I’ve returned to this moment more times than I can count—the pause Daniel Day-Lewis takes before uttering “people,” followed by that sudden fit of laughter. It gives me endless joy, but it also stirs a deep curiosity about his process, about what he was tapping into in that instant that made the response feel so alive and unpredictable.

The firelight makes it intimate. He’s not roaring, not blustering. He’s calm, almost resigned. And that makes it more unsettling. It’s not a speech designed to manipulate Henry—it feels like honesty, the kind of honesty Plainview rarely allows anyone to hear.

Daniel’s words at the campfire cut against the version of himself he usually performs—the genial family man for investors, the commanding oilman for rivals. In the glow of the fire, he strips that mask away and admits to a corrosive loneliness, surrounded by people he neither trusts nor respects. And when Henry’s true identity is revealed later, that brief thread of intimacy snaps, hardening Daniel’s conviction that no one is worth letting in and pushing him further into paranoia and violence.

It’s a pivotal moment because it articulates what the whole film is circling: Daniel’s success is fueled by misanthropy. His drive comes not from love of oil, or even love of his son, but from a need to dominate and shut the world out. Sitting by that fire, he tells us the truth—he has everything, and he has nothing.

Now unless you’re a film student, actor, writer, film obsessed in the way that some of us are, I understand it’s not feasible to watch film this way. But I do think there is a way to experience film and any art with one watch that allows us to get the most out of it. Which is what George Saunders was getting at in teaching us how to read story.

George Saunders teaches us that reading is an act of attention. In A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, he pauses mid-story to ask: What just happened? What do we expect to happen next? Why is the writer making this choice? It’s not about dissecting the story with jargon—it’s about reading slowly enough that you catch yourself reacting, and then getting curious about those reactions.

Watching film can work the same way. You don’t have to rewatch four times if you bring that Saunders-style attentiveness into a single viewing. Instead of just letting the film happen to you, you can stop (mentally, not literally) and notice:

What is the story asking me to feel right now?

What detail keeps pulling my eye?

Why did the filmmaker choose to cut here, or hold there?

What surprised me, and why?

This doesn’t mean pausing the movie with a notebook. It means carrying a quiet awareness into the experience—being present enough to register your own responses as the story unfolds. Saunders shows that stories are alive when we pay attention. Films are no different. The first watch can feel like the second, third, and fourth—if we slow down enough to listen, notice, and reflect.

I don’t know. This could all be just a convoluted way of me justifying having watched Boogie Nights thirty times or Goodfellas fifty times. But I do know that nobody knows anything. Especially in this industry. Because is subjective. And we all have our own way of processing art. For me, compartmentalizing helps me explore a piece of art the way my nerdy brain works. For you, it may be much simpler. Maybe you can fully understand everything a film, book, poem, song, painting is trying to saying upon one viewing or listen. And that’s awesome.

One thing I have learned in my life, that I know in the depth of my soul, to be true is:

Being open to exploration is what it’s all about.